Forces and motion

Motion

Constant acceleration equations

The constant acceleration equations use the following variables

- Final velocity

- Initial velocity

- Acceleration

- Time for the change in velocity

- Displacement during the velocity change

The final equation is not required for this course.

Free fall and projectile motion

Free fall The acceleration a body feels when falling in the presence of a gravitational field

Objects of different masses fall at the same rate under the influence of gravity, this is because the acceleration of a body is directly proportional to the net force, but inversely proportional to its mass.

Trajectory The path of any moving object

Projectile An object that is given an initial force, and then allowed to move freely through space

Parabola The name given to the shape of a curve which a projectile follows when gravity is the only force acting upon it

In the real world air resistance also acts on projectiles, however this is ignored in order to allow the problems to be solved using the constant acceleration equations.

To solve a problem, the components of motion are split into two parts, horizontal and vertical.

Measurement of g

Light gate A device which measures the time between a beam of light being broken and being restored.

Motion sensor Record displacement at regular time intervals

Both of these devices can be used to determine an experimental value for .

Measurements can either be direct or indirect

- Direct measurement is measurement which does not require manipulation, such as time a falling object

- Indirect measurement requires manipulation, such as measuring the period of pendulum and rearranging to find

When explaining an investigation, state the following

- The measurements to be taken

- The equipment with which to take the measurements

- The variables required to determine

- The sources of uncertainty in the measurements

- The possible methods to minimise uncertainty

Investigation- Use of a trap door and an electromagnet to determine

Equipment

An electromagnet supports a steel ball.

The electromagnet is on the same circuit as a timer.

Procedure

When a switch is toggled the ball begins to fall a known distance, and the timer on the same circuit begins.

The ball falls onto a trap door, stopping the timer.

Calculation

The variables are the distance fallen, s, and the time taken, t.

Using the constant acceleration acceleration

For any values of s and t we can then find a value for acceleration due to gravity.

Alternatively we could use the inferior and inaccurate method of drawing a graph of against which would have a gradient of .

Methods to increase accuracy and reduce error

In order to increase the accuracy of the experiment we could take repeat readings to find a mean value for , and measure t across different heights.

Car stopping distances

Stopping distance The total distance that a vehicle travels before it stops

Thinking distance The distance a vehicle travels between the operator seeing the hazard and applying the brakes

Braking distance The distance that a vehicle travels between its brakes being applied and it coming to rest

| Factors affecting thinking distance | Factors affecting braking distance |

|---|---|

| Reflexes | Poor road conditions |

| Drugs | Road surface |

| Tiredness | Problems with the vehicle |

| Distractions | Mass of the vehicle |

| Speed of the vehicle |

Force in action

Force and the Newton

Resultant force A single force which has the same effect as the sum of all forces acting on a body

Thrust A term used for the driving force provided by a jet engine

Drag A force which acts in the opposite direction to motion, impeding it. Also called the dissipative force

Types of forces

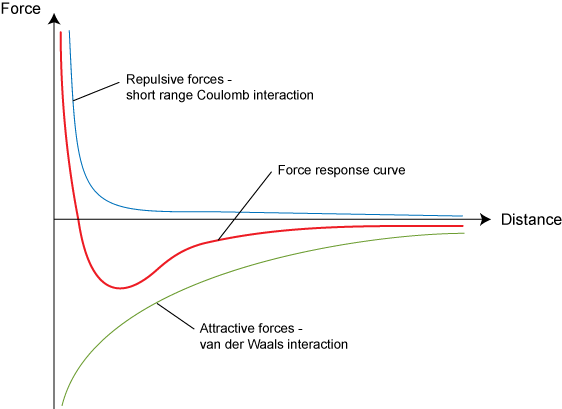

- Contact- Two bodies touch when their repulsive molecular forces equal the force that is trying to bring them together

- Friction- When two bodies are in contact their attractive molecular forces try to prevent their common surfaces moving relative to each other

- Tension- The force exerted by a body when it is stretched. It is due to attractive molecular forces

- Compression- The force exerted by a body when it is compressed. It is due to repulsive molecular forces

- Fluid upthrust- The force exerted by a fluid on a body because of the weight of the fluid that has been displaced by the body. Archimedes’ principle states that the upthrust force is equal to the weight of fluid displaced.

- Electrostatic- Attractive and repulsive forces due to bodies being charged

- Magnetic- Attractive and repulsive forces due to moving electric charges

- Electromagnetic- Attractive and repulsive forces due to bodies being charged. Contact, friction, tension, compression, fluid upthrust, electrostatic, and magnetic forces are all forms of electromagnetic foce

- Weak nuclear- The force responsible for nuclear decay

- Electro-weak- It is thought that both the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces are both forms of this fundamental force

- Strong nuclear- This fundamental force holds protons and neutrons together in the nucles

- Gravitational- The fundamental force exerted on a body due to its mass

Dynamics

Dynamics A branch of mechanics concerned with the motion of bodies under the action of forces

While dynamics is the study of the motion of bodies and the forces that cause the movement, kinematics is the study of movement without any reference to external forces.

The normal contact force, or reaction force, acts perpendicular to the point of contact against a surface.

When two surfaces move next to each other, each surface is slightly deformed, meaning that the bonds between the atoms are stretched and compressed.

Friction occurs within all fluids.

Free body diagrams

Free body diagrams help to determine the net force on a body

They should always contain

- The body or point upon which the forces are acting

- The direction in which each force acts

- The type of each force

- The size of each force

The diagram below shows the free body diagram for an object on a rough inclined plane

Drag and terminal velocity

Fluid A substance which has no fixed shape, and yields easily to external pressure

Any object which moves through a fluid experiences a dissipative drag force.

The drag force is called aerodynamic drag when the fluid is a gas, and hydrodynamic drag when the fluid is a liquid.

The frictional force on a body moving through a fluid is given by

Where

is the drag force

is the density of the fluid

is the coefficient of drag

is the cross sectional area of the object

is the velocity of the object

For an object of constant size, moving through a fluid of uniform density the drag force, , is proportional the the square of the velocity, .

Terminal velocity

When an object falls from a height, it initially accelerates because the force of gravity is greater than the resistive force.

As it accelerates, its velocity increases, and as such the drag force increases proportional to the square of the velocity (). The increase in drag force results in a decrease in acceleration.

When the drag force is equal to the force of gravity, the object is at terminal velocity.

Equilibrium

Equilibrium If the resultant force acting on an object is 0, the object is said to be in equilibrium

The resultant force can be found by splitting each of the forces acting on a body into their respective horizontal and vertical components, before finding the resultant in each axis.

Turning forces

The turning effect of a force is called a moment

Couple Two equal antiparallel forces acting to produce rotation with no linear motion

Torque The torque of a couple is defined as the moment or turning effect produced by a couple

The moment is the force multiplied by the perpendicular distance from the pivot around which it is acting

Principle of moments

The principle of moments states that when in equilibrium the sum of the clockwise moments is equal to the sum of the anticlockwise moments.

The resultant force must also be 0 to ensure that there is no translational acceleration.

Centre of mass

Centre of mass The centre of mass of an object is the single point at which all of an objects mass can be assumed to be situated. For a symmetrical body of uniform density it is always situated at the centre of the object.

Method for determining the mass of irregular shapes

- Make two holes in the objects

- Hang the object from each of the holes and draw a line from the hole parallel to the ground

- The centre of mass is the point at which the lines cross

Centre of gravity The centre of gravity is the single point through which the entire weight of the object can be thought to act

The stability of objects are determined by the position of their centres of mass and their base area.

Objects with a low centre of mass and wide base area are more stable.

Density

Density The mass per unit volume of a substance

Pressure

Pressure The force per unit area

For hydrostatic pressure

Where

is the depth of the fluid

is the density of the fluid

is acceleration due to gravity

Work, energy, and power

Work and the joule

Work The work done is the product of the force and the distance moved by the force in the direction of movement

One joule is defined as the energy exerted when a force of one newton is applied over a displacement of one metre.

The area under the curve of a force-distance graph is equal to the work done

The conservation of energy

Forms of energy

- Kinetic energy- Energy possessed by a moving body

- Nuclear energy- Energy transferred during a nuclear reaction

- Gravitational potential energy- Energy possessed by anything under the influence of a gravitational force

- Elastic potential energy- Energy possessed by an object which has been stretched

- Chemical energy- Energy stored in the bonds of a molecule

- Electrical energy- Energy due to the flow of electrons

- Light energy- Energy possessed by electromagnetic radiation

- Sound energy- Energy possessed by sound waves

- Radiation- Energy transferred by heated object in the infrared spectrum

1st law of thermodynamics

Energy cannot be created or destroyed in an isolated system

2nd law of thermodynamics

The entropy of any isolated system always increases

3rd law of thermodynamics

The entropy of a system approaches a constant value as the temperature of the system approaches absolute zero

Potential and kinetic energy

The kinetic energy, possessed by an object in motion is given by

The gravitational potential energy, GPE, stored in an object by virtue of its position in a gravitational field is given by

When an object falls under the influence of a gravitational force, its gravitational potential energy is converted into kinetic energy.

When an object is launched upwards with an initial velocity, and therefore an initial kinetic energy, its kinetic energy is converted to gravitational potential energy until it has 0 velocity, and begins to fall.

Power and the watt

Power The rate of work done

The power produced by an object moving at speed v under a force F produces a power given by

Efficiency

Efficiency The efficiency of a process is the ratio of useful work performed to the total energy expended

Materials

Deformation of materials

Deformation The change in shape or size of an object

Elasticity The tendency of a body to resume it’s original shape or size once a deforming force or stress has been removed

Elastic deformation When a body returns to it’s original shape once a stress, strain, or force is removed

Plastic deformation When a body does not return to it’s original shape once a stress, strain, or force is removed

Tensile forces

Tensile forces cause tension in an object.

If there is tension in a wire, then there must be an equal and opposite force at both ends.

These forces will cause the wire to increase in length, a positive extension.

Compressive forces act towards each other and have the opposite effect.

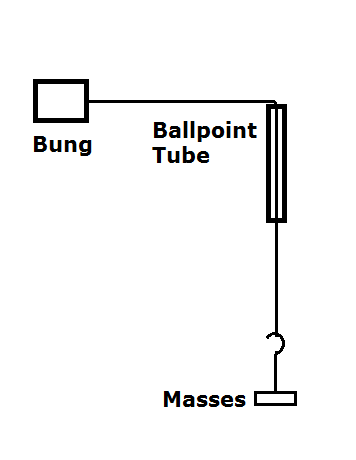

Measuring the stretch of a wire

- Attach a wire to a clamp

- Run the wire horizontally, over the edge of a surface through a pulley

- Attach mass to the wire so that it is taught

- Place a mark on the wire, and a ruler underneath it inline with the mark

- Progressively add more mass, measuring how far the mark moves

Elastic limit

The important points are

- The limit of proportionality

- The elastic limit

- The fracture point

- The plastic deformation region

Hooke’s law

Hooke’s law The extension of an object is proportional to the force that causes it, provided that the elastic limit is not exceeded

Hooke’s law states

The force (N) is equal to the spring constant multiplied by the extension .

Springs in series and combination

When springs are suspended in series, each spring experiences the same pull from the weight of the mass it supports. Therefore each spring extends the same amount as an individual spring would do.

When springs support a weight by combination, they share the load and therefore are not stretched as much as if they were supporting the weight themselves.

Force extension graphs and work done

As stated previously, work done = force x distance.

Therefore, the area under a force-extension graph is equal to the work done in applying the extension.

This work done is equal to the elastic potential energy stored within the extended object.

Prior to the limit of proportionality, the area under the curve forms a triangle

as , we also have

Usually we plot the independent variable on the x-axis, and the dependent on the y-axis.

Force extension graphs break this convention.

If we plot extension on the x, the gradient is then the spring constant

The Young modulus

Stress Force per unit area Given the symbol

Strain Extension per unit length (Unitless) Given the symbol

The young modulus is the ratio of stress to strain

A stiff material needs more force to deform in comparison to a soft material. The Young’s modulus is a measure of the stiffness of a solid.

Strength The amount of force that a material can withstand and still recover its original shape

Hardness The relative resistance that the surface of a material imposes against the penetration of a harder body

Toughness The amount of energy that a material can absorb before fracturing

As we know that

and

we can write the Young’s modulus as

Investigating Young modulus

Searles apparatus

- Measures the original length of a wire before any load

- Measures the diameter of the wire with a micrometre

- Force of tension is then increased by adding masses to the right side

- Extension is measured after each new mass is added

- A stress vs strain graph is plotted from the data

With a ruler and mass

- Attach a wire to a clamp

- Run the wire horizontally, over the edge of a surface through a pulley

- Attach mass to the wire so that it is taught

- Place a mark on the wire, and a ruler underneath it inline with the mark

- Progressively add more mass, measuring how far the mark moves

Use the collected values to calculate the Young modulus of the wire

Ultimate tensile strength The maximum stress a material can withstand while being pulled or stretched before it breaks

Elastic hysteresis The process in which energy is dissipated by the loading and unloading of a material

Categorisation of materials

Ductile A ductile material can be drawn into wires and will show plastic deformation under tensile stress before it breaks

Malleable A malleable material can be hammered and beaten into flat sheets and will show extensive plastic deformation when subjected to compressive forces

Brittle A brittle material will break with very little plastic deformation

Polymeric A polymeric material has long chains of molecules that allow for elastic deformation

When a ductile material is stretched, it will increase in length and decrease in cross sectional area to compensate for this. This process is known as necking.

Newton’s laws of motion

Three laws of motion

Newton’s first law

A body will remain at rest or continue to move at constant velocity until an external force acts upon it.

Newton’s second law

The resultant force on an object is proportional to the rate of change of momentum, when the change in momentum takes place in the direction of the force.

Newton’s third law

For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction

Momentum

Linear momentum The mass of an object multiplied by its velocity

Conservation of momentum The total momentum before a collision is always equal to the total momentum after a collision, provided that no external forces are involved

Force and impulse

Elastic and inelastic collisions

Elastic collision A collision in which the momentum and the kinetic energy are conserved. No energy is transferred to any other forms

Inelastic collisions A collision in which momentum is conserved but some of the kinetic energy is transferred to to other forms in the collision

Electrons, Waves, and Photons

Electricity, charge, and current

Electric circuit components

All electric circuits require the following

- An energy source- A source of electromotive force

- A closed path or complete circuit- For electrons to flow in a complete loop from a negative electrode to a positive electrode

- Electrical components

Conventional current Behaves as if the positive charge carries cause current flow from the positive terminal to the negative terminal

Electron flow As electrons are negatively charged, they flow from the negative electrode to the positive electrode

Electric current and charge

Electrons protons and neutrons have mass and charge

| Mass | Charge | |

|---|---|---|

| p | ||

| n | ||

| e |

These are normalised to

| Mass | Charge | |

|---|---|---|

| p | 1 | +1 |

| n | 1 | 0 |

| e | 0 | -1 |

Electric current The rate of flow of charge

This can also be written as

where n is the number of electrons.

The unit of charge is the coulomb ().

One coulomb is the quantity of charge that passes a fixed point in one second when a current of one ampere is flowing

Kirchhoff’s first law

At any junction in a circuit, the sum of the currents arriving at the junction is equal to the sum of the currents leaving the junction.

Electron drift velocity

Electrons move in random directions.

When a current is flowing, the electrons have a mean velocity in the direction of electron flow.

Calculating electron drift velocity

where q is the charge on each charge carrier

Power, energy, and resistance

Potential difference and E.M.F

The difference between potential difference and electromotive force

p.d can be measured in several places in a circuit, across each of its components. It is the energy transferred per unit charge as they pass through the component.

e.m.f is only associated with the electrical energy source. It is the energy gained per unit charge passing through the source.

Mathematically they are the same, because they are both measured in volts.

Resistance and Ohm’s law

Ohm’s law

The current through a conductor is directly proportional to the potential difference across it, provided that physical conditions, such as temperature, remain constant.

Resistance

Resistance The ratio of voltage applied to a material to the current which flows through it ()

Resistance depends upon the type of material, and the volume of the material.

Longer wires will have a smaller potential gradient. The longer the wire, the lower the ‘voltage per metre’. This will lower the drift velocity and hence result in a smaller current.

This means that the resistance of the wire increases in direct proportion to the length of the wire.

Resistance is inversely proportional to the cross sectional area of the wire. There is no change in potential gradient, but there is a large volume of electrons that are available to flow at the same drift velocity.

Resistance also depends on the temperature of the wire.

When the temperature increases, the fixed metal ions vibrate more creating an obstacle for the flow of electrons.

Resistivity

Resistivity A measure of the resisting power of a material to the flow of electric current through it

Resistivity applies to a particular component.

While resistance is measured in ohms , resistivity is measured in ohm metres

where

= resistivity

= resistance

= area

= length

The effect of temperature on resistivity

where

= resistivity of the material at temperature

= resistivity of the material at temperature

= the temperature coefficient

= the temperature of the material

The reference temperature at which the resistivity of the material is quoted (Usually room temperature)

Electrical power

The cost of electrical energy

Kilowatt-hour The kilowatt hour () is a unit of energy used by electricity companies in the context of billing household customers

1 kilowatt hour is the energy expended by a task drawing 1 kilowatt of power for 1 hour.

Kirchhoff’s first and second laws

Kirchhoff’s first law

At any node in an electrical circuit, the sum of currents flowing into that node is equal to the sum of the currents flowing out of that node

Kirchhoff’s second law

The directed sum of the potential differences around any closed network is zero.

More simply, the sum of the e.m.fs around a circuit is equal to the sum of the potential differences.

Electric circuits

Series circuits

Resistance in series circuits

The total resistance of a set of resistors in series is equal to the sum of the individual resistances of the resistors

Current in series circuits

The amperage at any point in a series circuit is the same

Voltage in series circuits

The voltage applied in a series circuit is equal to the sum of the individual voltage drops

Parallel circuits

Resistance in parallel circuits

The reciprocal of the total resistance in a parallel circuit is equal to the sum of the reciprocals of the individual resistances of the resistors

Current in parallel circuits

The sum of the currents in the branches of a parallel circuit are equal to the total current of the circuit

Voltage in parallel circuits

The voltage across each component s the same as the voltage of the battery.

Ammeters and voltmeters in circuits

Ammeters

Ammeters are always connected in series with components to measure the size of the current flowing through them. Ammeters are designed to have negligible resistance.

Voltmeters

Voltmeters are always arranged in parallel with components in a circuit. They are designed to have close to infinite resistance so that none of the current flows through them.

The potential divider

Potential divider A circuit which uses two resistors to split up or divide the voltage of the supply in a chosen ratio

The size of the output voltage is given by

The ratio of the potential differences across each of the resistors is equal to the ratio of the resistances of the resistors.

Using a variable resistor

The potential divider can be used with a variable resistor across the output voltage, allowing to be easily adjusted.

Using a thermistor in a temperature control circuit

If a thermistor is used across the circuit can be used to control a heater on an on/off cycle.

Using a light-dependent resistor in an illumination control circuit

An LDR has a high resistance when the incident light intensity is very low. As the intensity of the falling light increases the resistance falls.

This means that the LDR can be used to switch lights on as the incident light decreases.

Internal resistance

Internal resistance The internal resistance of a source of e.m.f is the resistance to electric current of the materials inside a cell

Terminal p.d The potential difference recorded across the terminals of a cell.

Lost volts The difference between e.m.f and the terminal p.d when charge flows in a cell

So when no current flows, and

The e.m.f and internal resistance of a cell are constant values. It is therefore possible to have a situation in which different currents will flow for different load resistances.

The values can be solved using simultaneous equations.

Finding the internal resistance of a cell

I we rearrange and substitute for we have .

This equations has the form , so if we plot a graph of against we will have a straight line with negative gradient and positive intercepts.

The intercept will be equal to the e.m.f of the cell.

The gradient of the graph equals the internal resistance of the cell.

Circuit analysis

Analysis of series and parallel hybrid circuits

Many circuits have a parallel branch that is connected in series with other components.

It is helpful to calculate the resistance of the parallel network first, before adding it to the resistance of the other components that are connected in series with it.

Series circuits involving two sources of e.m.f

If two sources of e.m.f have opposite polarities the overall e.m.f can be found by taking one source to be the negative direction and summing them.

Parallel circuits involving two sources of e.m.f

The overall e.m.f available to the circuit can be found in the same manner as for a series circuit.

To calculate the combined effective resistance of the network, arrange as would normally be done for a parallel circuit.

Waves

Wave motion

Waves transfer energy from one place to another without any net transfer of matter.

Waves can be longitudinal or transverse.

In longitudinal waves the vibrations are parallel to the direction of energy transfer, resulting in the formation of compressions and rarefactions.

In transverse waves the vibrations are perpendicular to the direction of energy transfer.

Progressive waves Waves which transfer energy away from a source

Wave terminology

Wavelength The wavelength, of a wave is the distance between two successive identical points that have the same pattern of oscillation.

Period The period, , is the time taken for the wave to complete one pattern of oscillation

Frequency The frequency, , is the number of oscillations per unit time at any point. It is the inverse of the period of the wave

Displacement The displacement, , is the distance of any part of the wave from its mean position

Amplitude The amplitude, , is the maximum displacement that the wave reaches from its mean position

Phase difference The phase difference, , the difference in the pattern of vibration between two points in the wave. Two points that have exactly the same pattern of oscillation are said to be in phase, there is zero phase difference between them

Using an oscilloscope

An oscilloscope displays a voltage-time signal and can be used as a voltmeter to display and measure the output from a microphone or signal generator.

The frequency of a wave displayed on an oscilloscope can be determined if you know the settings of the time base on the oscilloscope.

This is the time taken for the luminous dot produced by the CRT to move a horizontal distance of 1cm across the oscilloscope’s screen.

Oscilloscope controls

Each horizontal division on the oscilloscope represents a unit of time. The time base control varies the seconds or milliseconds per division.

The uncertainty in the frequency measurement can be reduced by altering the time base such that one full wave has the widest possible range in the x direction.

If the time base is turned off, the spot no longer moves across the screen. This is useful for observing the intensity of the wave.

Each vertical division on the oscilloscope screen represents a unit of voltage. The sensitivity control varies the volts per division.

Wave speed and the wave equation

The wave equation

can also be applied to movement

In a time equal to one period, , the wave travels one wavelength, . Therefore the speed, , of the wave is

We know that the frequency is the reciprocal of the period, so this can also be written

Energy transfer by waves

A progressive wave transfers energy from one place to another. From a point source producing waves, this energy spreads out in all directions.

Intensity Power per unit area

The intensity is given by

If the power spreads out equally in all directions this can be written

Intensity and amplitude

The amplitude of a wave decreases as the wave spreads out from a source.

The energy of a wave is proportional to the square of its amplitude. Hence the intensity of a progressive wave is also proportional to the square of its amplitude. $I \propto A^2 $

Common properties of waves

Reflection

All waves can be reflected.

Ray A single line to illustrate the direction of a waves travel. Rays are always drawn at right angles to the wavefronts.

Refraction

Refraction occurs when a wave moves from one material into another.

In terms of refraction of light, we say that the two materials have different optical densities.

Two observations an be made when refraction occurs

- The wave will change its speed

- There may be a change in direction

Investigating refraction and reflection in a ripple tank

In a ripple tank, a motorised straight edge bar produces plane waves, while a small dipper produces circular waves.

When light is shone from above through the waves produced, the bright bands or curves of light seen on on the screen below the tank show the wave crests. This makes it possible to measure the wavelength of the water waves, and investigate the angles of reflection and refraction.

Reflection at plane and curved surfaces can be investigated, and the angles of incidence and reflection measured with respect to the normal.

A glass sheet is used to decrease the water depth and so produce a region with a different wave speed. The water level can also be adjusted.

If the separation of the wavefronts decreases this shows they are travelling more slowly. If the wavefronts are at non-zero angle when they cross the barrier, the waves also changes direction.

Diffraction

Diffraction The spreading out of a wave after passing around an obstacle or through a gap

Diffraction is most pronounced when the wavelength of the wave being diffracted is the same size as the gap that they are travelling through.

Interference

Interference The addition of two more more waves (superposition) that results in a new wave pattern

Electromagnetic waves

Common properties of electromagnetic waves

The electromagnetic spectrum has a range of values for wavelength of to .

Visible light is a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum ranging from approximately for violet to for red.

All electromagnetic waves share the following properties

- They can travel through a vacuum

- They possess both a magnetic wave and an electrical wave interlocked perpendicular to each other

- They travel at the speed of light in free space,

- They are all transverse waves

- They can all be reflected, refracted, and diffracted

- They can all demonstrate interference

- They can all be polarised

| Wavelength (m) | Frequency (Hz) | Method of production | Method of detection | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| to | to | Electrons oscillated by electric fields in aerials | Resonance in electronic circuits | TV, Radio, and telecommunications |

| to | to | Magnetron, klystron oscillators, using electrons to set up oscillations in a cavity | Heating effect, electronic circuits | Radar, mobile phones, microwave ovens, satellite navigation |

| to | to | Oscillation of molecules, from all objects at any temperature | Photographic film, thermopile, heating of skin | Heaters, night vision, remote controls |

| to | to | From high temperature solids, gases, and lasers | Photographic film, the retina | Sight, communication |

| to | to | From high temperature solids, gases, and lasers | Photographic film, phosphors, sunburn | Disco lights, tanning studios, counterfiet detection, detergents |

| to | to | Bombarding metals with high-energy electrons | Photographic film, fluorescence | Computer-aided tomography scans, X-ray photography, crystal structure analysis |

| to | to | Nuclear decay or in a nuclear accelerator | Photographic film, Geiger tube | Diagnosis and cancer treatment |

Non-ionising electromagnetic radiation

Radio waves, microwaves, and visible light do not have enough photon energy to remove electrons from the shells of atoms. For this reason they are deemed to be relatively safe.

Ionising electromagnetic radiation

Ultraviolet rays, X-rays, and gamma radiation all have high photon energies. This means that they can cause ionisation.

This can lead to human cell mutation and is therefore dangerous.

Ultraviolet radiation emitted by the Sun is often divided into three regions

- UV-A 315-400nm causes tanning when skin is exposed. Accounts for 99% of UV light

- UV-B 280-315nm causes damage such as sunburn and skin cancer

- UV-C 100-280nm filtered out by the atmosphere and doesn’t reach Earth

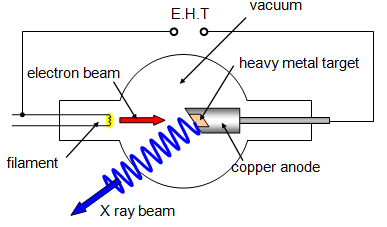

Production of X-Rays

Polarisation

Plane polarised wave A wave in which the oscillations of the field and the direction of travel are confined to a single plane

Polarising filter A filter which produces plane-polarised waves by selective absorption of one component of the incident oscillations.

Rotating the plane of polarisation

A second polariser called the analyser an be used to rotate the plane of the waves polarisation to a direction parallel to its long edge.

If the amplitude of the light wave approaching the analyser sheet is A, then after it has had its plane of polarisation rotated by angle the amplitude will be .

Because the intensity of a wave is proportional to its amplitude squared, the intensity after the analyser is proportional to .

This is know as Malus’ law.

It states that when a perfect polariser is put in a beam of polarised light, the intensity, , of the light that passes through it is given by , where is the intensity transmitted at angle .

Also is the maximum intensity transmitted (at ).

This law also shows that if the analyser is at right angles to the polariser no light will pass through. This situation is known as ‘crossed polaroids’.

Uses of polarisation

Polarisation can be used for strain analysis. Certain plastics, such as those used for making rulers, protractors and Sellotape, contain long chains of molecules which become aligned during manufacture.

These materials are able to rotate the plane of polarisation so that the transmitted light is polarised.

When these plastics are placed between two crossed polaroids, coloured images are produced that change as the plastics are stretched or squashed. This is because the rotation of the plane of polarisation is different for different wavelengths.

Refraction of light

For all types of electromagnetic radiation, the speed of the wave will decrease as it moves from a material of lower refractive index into a material of higher refractive index.

The speed of an electromagnetic wave in a material is related to the refractive index of the material by

A vacuum has a refractive index of 1, and air has a refractive index of 1.00028 ≈ 1.

Snell’s law

There is a link between the refractive indices of two materials and the directions at which the incident and refracted rays will travel with respect to the normal.

An electromagnetic wave travelling at an angle, , to the normal in a material, , will travel at an angle, , to the normal in a second material, .

This is explained by Snell’s law, which is given by

or that

The angle of incidence and the angle of refraction are always measured to the normal line, not to the boundary.

Total internal reflection

Total internal reflection The complete reflection of a light ray reaching an interface with a less dense medium when the angle of incidence exceeds the critical value.

The critical angle

In the specific case of total internal reflection between two materials, we know that is the refractive index of the material of higher refractive index.

is the sine of the critical angle.

The critical angle is given by

The ratio of to must be less than 1, so . The smaller refractive index must be .

Determining the critical angle for a transport material

To determine the critical angle of a material, use a semicircular shaped block of the material.

Draw around the shape on a piece of paper, making a mark at the centre of the straight edge and draw a normal at that point.

Shine a ray from a ray box towards the curved edge of the block in an arc until the ray emerges along the surface of the boundary between the material and air.

The angle the ray makes with the normal is the critical angle.

The critical angle can be used to find the refractive index of the material in question using

Interference

The principle of superposition

The principle of superposition states that when two or more waves of the same type meet, the resultant wave can be found by adding the displacements of the individual waves.

Interference

If two waves, A and B, with the same amplitude exist at the same point and are travelling in phase, the amplitude of the resultant wave will be twice that of the individual waves. This is constructive interference.

If the waves are in antiphase they will cancel each other out. This is destructive interference.

Coherence

Generally, waves will not be in perfect phase or antiphase.

So long as the two waves have a constant phase difference, they are coherent.

Path difference The path difference is the difference in metres between the lengths of two paths. It is often written in terms of the wavelength of two the wave

Phase difference The phase difference is the difference in radians of the phases of two waves of the same frequency

| Path difference | Phase difference | |

|---|---|---|

| Constructive | Integer number of wavelengths e.g. 0, λ, 2λ, … | 0, 360, 720, … or 0, 2π, 4π, … |

| Destructive | Odd number of half wavelengths e.g. λ/2, 3λ/2, … | 180, 540, 900, … or π, 3π, 5π… |

Interference using sound waves

Interference using sound waves can be demonstrated using two loudspeakers connected to the same signal generator. As you walk in front of the loudspeakers you will hear a loud sound where the sound waves reinforce one another, and a quiet sound where the waves partially cancel one another out.

This variation is clear if you cover one ear.

The distance between the loud and quiet regions is longer for lower frequencies.

The Young double-split experiment

The coloured patterns patterns seen on an oil spill on water are a result of the interference of light waves.

In order to make measurements of the wavelength of light, two conditions must be satisfied

- The light must be monochromatic

- There must be an accurate method of producing very small path differences, and of measuring these differences

The experiment

Light is produced by a monochromatic source and diffracts outwards, before reaching a second set of two narrow parallel slits.

The light from these two slits is coherent because it comes from a single slit.

When the waves reach an obstacle, alternate bright and dark vertical bands or ‘fringes’ will be seen.

For optimal results, the experiment should be carried out in a darkened room.

To reduce percentage error in the fringe separation it is best to measure across all the fringes and then divide by the number of fringes.

Increasing the distance from the slit to the screen will increase the fringe separation, but reduces light intensity at the screen.

Finding the wavelength of the light source

For constructive interference to take place, the path different must be a whole number of wavelengths.

For destructive interference to take place, the waves must arrive out of phase with path difference of half a wavelength.

In the diagram above, the two triangles are a similar shape, so their angles are equal.

If θ is the angle away from the central fringe

If the angle is small enough so

The equation only applies if , or the angle away from the fringe is less than 10°.

The diffraction grating

A diffraction grating is a piece of optical equipment made from glass, onto which many thousands of thin, parallel, and equally spaced grooves have been engraved using a diamond.

Light that passes through the grating will be diffracted at different angles based on the wavelength of the incident light and the separation of the grooves.

Multiple slits

It is difficult to accurately determine wavelengths using the Young double-slit experiment. The diffraction fringes are quite blurred, which makes measuring the fringe width difficult.

This can be overcome by using multiple slits.

Increasing the number of slits that the light has to pass through improves the brightness and sharpness of the maxima and makes it easier to measure an accurate value for the wavelength of light.

The maxima are also further apart, so the angle can be measured with a lower percentage uncertainty.

Because the length of n wavelengths, , must be equal to , we get the diffraction equation

where n is called the order of the maximum, is the wavelength of the incident monochromatic light, is the separation of the slits in the grating, and is the angle that the beam makes with the grating.

Measuring the wavelength of light using a diffraction grating

The wavelength is found using . If the grating has slits per metre the slit spacing, , is the reciprocal of this value.

The angle is found with a protractor. The percentage uncertainty in is decreased if is as large as possible. This occurs for smaller slit separations and also for higher order fringes, however the intensity of the higher order fringes is lower, making them difficult to locate.

could also be found geometrically, using , where is the distance from the central maxima and is the distance of the grating from the screen.

Stationary waves

It is possible to confine a wave, and its energy to a fixed position. These waves are called standing or stationary waves.

Examples include waves on strings, such as stringed instruments, and air columns in tubes or pipes.

Formation of stationary waves

Stationary waves are produced by interference in accordance with the principle of superposition.

In order for a stationary wave to be produced on a string or in a pipe, the two waves that overlap must be travelling in opposite directions, have the same frequency, and approximately equal amplitudes.

The process

- Initially there are two progressive waves moving in opposite directions

- The two waves are in antiphase, with a phase difference of 180° or π rad

- This leads to a resultant wave of amplitude zero

- As the waves move, they move into phase and they create constructive interference to produce a wave with an amplitude equal to the sum of the amplitudes of the individual waves

- The wave pattern for a whole cycle returns the waves to their original states

Node A node in a stationary wave is a point at which there is no displacement of the particles at any time

Antinode An antinode in a stationary wave is a point at which the displacement of the particles varies by the maximum amount

Stationary wave experiments

Stationary waves on strings

The frequency of vibration of a string is governed by

- Its mass per units length

- Its tension

- The length of the string

The effect of bowing a violin string is to create progressive transverse waves that travel in opposite directions along the string away from the bow. When these waves reach the points where the string is fixed to the body of the violin, they are reflected back along the string. They then interfere with each other producing a stationary wave.

A stationary wave in a guitar string obeys the equation

where

is the frequency of vibration ()

is the length of the string ()

is the tension in the string ()

is the mass per unit length of the string

Fundamental mode of vibration and harmonics

The simplest type of stationary wave on a string is a wave with a wavelength equal to twice the length of the string.

This type of oscillation is called the fundamental mode of vibration. The fundamental frequency is the lowest frequency, highest wavelength that can be produced on a string. However other notes of higher frequency can also be produced, and these are called harmonics.

The frequency of a harmonic is always an integer multiple of the fundamental frequency.

Stationary longitudinal waves

Stationary waves in closed tubes

A stationary longitudinal wave is a specific type of stationary wave, created by blowing across one end of a tube.

As with the stationary wave produced on a string, the stationary wave in the tube is produced when progressive waves travel in opposite directions through one another.

A progressive wave can be started at one end of a closed tube by blowing across the open end. This wave travels down the tube and is reflected at the closed end. This produces two progressive waves travelling in opposite directions, which then interfere to produce a stationary wave.

However, to produce a stationary wave the length of the tube must be such that a node is formed at the closed end, and an antinode at the open end.

Stationary waves in closed tubes

The sound wave will also be reflected at the open ends of a pipe. Since the tube is open at both ends, each end is an antinode.

Measuring the speed of sound in air

The speed of sound in air can be measured using a tuning fork and a tube of water.

The tube is held by a clamp and is movable so that its length can be altered. Because of the water in the measure cylinder, the tube is effectively closed at one end.

When a tuning fork of known frequency is struck and held at the open end, air molecules in the tube will vibrate and a stationary wave will be set up in the table.

By listening carefully, the fundamental frequency can be obtained, when the sound is loudest at the minimum length. This is achieved when the length of the tube is equal to one quarter .

The tube can then be lengthened by loosening the clamp, and the loudness of the sound will reduce initially before increasing again to a second maximum loudness when the length of the tube is equal to . The difference between these two lengths is equal to half the wavelength of the sound, , and the speed of sound can be determined by multiplying this value by two, and then by the frequency of the tuning fork.

Quantum physics

The photon

Quantum A small discrete unit of energy

Photon A quantum associated with electromagnetic radiation

Planck constant The Planck constant, , has a value of . Photon energies are always emitted in multiples of this value

The equation relating the speed of light, , the frequency of the wave, , and its wavelength, , is

or

Rearranging this equation and substituting gives an alternative equation for calculating the energy of a photon

Using LEDs to determine a value for the Planck constant

LEDs come in a range of colours. Because the colour or wavelength of the light being emitted is related to photon energy, we can use different LEDs to determine a value for the Planck constant.

We need the following equipment

- Four LEDs of different colours and known wavelenghts

- A DC power supply

- An ammeter and a voltmeter

- A resistor

The apparatus is set up with the LED, power supply, ammeter and resistor in series, and the voltmeter in parallel across the LED.

We can then measure the current flowing as we increase the p.d across the LED by adjusting the variable resistor. Obtain at least six values for and , in steps of over the range where the LED starts to emit light.

We then determine the activation voltage for each LED.

Using these values to plot a graph of activation voltage against the reciprocal of the respective wavelength, we achieve a graph with a gradient of

The energy of a photon is equal to the energy of the electrons that are excited in the semiconductor material of the LED

which can be rearranged to

Comparing this to the form of a straight line graph, we can see that is the gradient of the graph multiple by a constant

If we measure the gradient of the graph of activation voltage against the reciprocal of wavelength, and then multiply by the charge on an electron before dividing by the speed of light, we find a value for .

The electronvolt

Electronvolt The kinetic energy gained by an electron when it is accelerated through a potential difference of 1 volt

We calculate the energy gained by an electron using

or

The charge on an electron is and the potential difference is , so .

The photoelectric effect

When electromagnetic radiation of a particular frequency is shone on the surface of a metal, electrons are emitted from its surface.

This phenomenon is known as the photoelectric effect, and electrons that are released are called photoelectrons.

Demonstrating the photoelectric effect with a gold-leaf electroscope

The gold-leaf electroscope is composed of a brass stem to which a thin gold leaf is attached. There is a metal cap attached to the top of the stem and the metal to be irradiated with electromagnetic radiation is placed on the metal cap.

A metal plate (usually zinc is placed on the metal and is then charged negatively by touching it with a negatively charged polythene rod, or by electrostatic induction.

When this is done the metal stem and gold leaf will also become negatively charged, meaning that the stem and the leaf will repel each other.

It is also possible to make the zinc plate, metal stem, and the gold leaf positively charged.

Observations of the photoelectric effect

When visible light is incident on a positively charged metal plate, there is no movement of the gold leaf. The same is also true when UV light is shone on the positively charged plate.

Shining visible light on the negatively charged zinc plate also causes no movements in the gold leaf. No matter how bright or intense the visible light is, no movement of the gold leaf is observed.

However, when UV light is shone on the negatively charged zinc plate, the gold leaf falls.

This shows that the metal plate loses its negative charge through the emission of electrons, which are repelled by the negative charge on the electroscope. The discharge of the electroscope cannot be caused by ions in the air, because the electroscope is in a sealed vacuum.

Further experiments show that

- Electrons will be emitted from the surface of a metal only if the incident radiation is above a minimum frequency called the threshold frequency. This is determined by the metal itself. Below this frequency, no electrons are emitted.

- Emission of electrons starts the instant the surface starts to be irradiated, provided that the incident radiation exceeds the threshold frequency.

Threshold frequency The lowest frequency of radiation that will result in the emission of electrons from a particular metal surface

Explaining the photoelectric effect

The work function

In order for electrons to be released from the metal, the frequency of the incident radiation must exceed the threshold frequency. This is needed to provide at least the minimum energy required to release an electron from the surface.

Work function The work function of a metal is the minimum energy required to release an electron from its surface, overcoming the electrostatic attraction between the electron and the positive metal ions

When an incident photon collides with the metal

- If there is no emission of electrons

- If an electron is released, but it has zero kinetic energy

- an electron with is released from the metal surface

As the intensity of the radiation is increased, more electrons are released, but their kinetic energy does not increase.

Calculations with the photoelectric effect

Determining the maximum kinetic energy of photoelectrons

We can equate the work done to accelerate or decelerate charged particles with the kinetic energy transferred to the electrons

At the stopping potential, all the emitted electrons have been brought to rest, so we obtain a value for the maximum kinetic energy of the photoelectrons by multiplying the stopping potential by the charge on an electron, .

Rate of emission of electrons

- The number of emitted photoelectrons is directly proportional to the intensity of the incident radiation, provided that the radiation is of a single frequency and is above the threshold frequency

- The kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectrons is not affected by the intensity of the incident radiation

- The kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectrons is affected by the frequency of the incident photons. If the frequency of the incident radiation is increased, the kinetic energy of the photoelectrons also increases

Millikan’s photoelectric experiment

Millikan irradiated the metals sodium, potassium, and lithium with monochromatic light. By applying a positive potential to the target metal, he could decelerate the electrons.

He increased the size of the potential until the most energetic electrons were unable to reach the cathode, causing the current to fall to zero.

This enabled him to determine the stopping potential, , of each metal, and show that this depends on the frequency of the radiation.

Not only did Millikan’s experiment obtain accurate values for the work functions of the metals, it also obtained an accurate value for Planck’s constant.

We know that

and

If we divide both sides by the electron charge, e, and rearrange for we have

This equation is of the form , meaning that if we plot a graph of stopping potential, , against frequency, , we will have a graph of gradient over , and a intercept equal to .

If we measure the gradient and multiply it by , we get a value for Planck’s constant.

If we read the intercept and multiply by , we get a value for the work function of the metal.

Wave particle duality

The wavelength of electrons

De Broglie proposed that if electrons and other particles travel through space as a wave, they have an associated wavelength. By combining the idea of an energy quantum with he derived a formula for the wavelength, , of a particle

where is the mass of the particle, and h is the Planck constant.

This equation was confirmed by observing the behaviour of electrons that had been diffracted from the surface of a nickel crystal.

By accelerating electrons, of charge e, through a potential difference , they observed a pattern of electron diffraction from which they could calculate the electron’s wavelength.

The predicted wavelength is found by equating the work done to accelerate the electrons with the kinetic energy transferred into the electrons

Substituting

into the de Broglie equation gives

Wave-particle duality for matter

The experiment confirming De Broglie’s results shows that matter could exhibit wave properties. According to De Broglie’s equation, all moving objects have a wavelength, including solids.

The greater the mass of the object, the shorter the wavelength, and macroscopic objects have such small wavelengths that their effects are negligible.

In modern physics, the wave nature of a particle is considered a probability wave. It represents the probability of an observer measuring a particle at a given place and time.

Newtonian World and Astrophysics

Thermal physics

Temperature

Kinetic model of matter A model allowing us to explain the properties of matter and changes of phase in terms of the arrangement of the particles, their motion, and the attractive forces between them

Atomic or molecular spacing

The density of any substance in kilograms per metre cubed is given by

density () mass of one molecule ) number of molecules per cubic metre ()

The mass of one molecule of water is the same for all three phases, so the density is directly proportional to the number of molecules per cubic metre.

Assume that the molecules behave like small spheres.

Placing them in a cube of volume 1 metre cubed.

If the distance between is , then the number along one edge is and the number in the entire box is .

More generally, suppose there is a volume of a substance composed of molecules.

We have

Example

of copper contains atoms of copper. Copper has a density of at room temperature.

Estimate:

The number of copper atoms present in of copper

The number of copper atoms present in of copper

The diameter of a copper atom

Using the previous answer we have giving and finally

Change of phase

Changing phase requires either an input of energy of a removal of energy.

Heating a solid will cause it to melt and become a liquid. Further heating of the liquid will cause it to evaporate and become a gas.

This is due to the energy of the particles increasing as energy is supplied. The extra energy results in the particles moving further and further apart until they have enough energy to overcome the forces of attraction to their adjacent particles.

Conversely, removing thermal energy from a system will reduce the energy of the particles causing them to move closer together, leading to condensation and freezing.

Internal energy

Internal energy the sum of the randomly distributed kinetic and potential energies of all the atoms or molecules within a system

The kinetic energy of the system is due to the movement of the particles within the system.

The potential energy of the system is stored in the bonds and inter-molecular forces that exist between the particles.

This stored energy will be released when the attractive forces between particles are overcome, such as during melting or evaporating.

Internal energies for solids and liquids

In solids, the particles’ kinetic energy is usually in the form of vibrational motion as the particles each oscillate about their respective equilibrium separations. This gives varying kinetic energy.

The total internal energy is the sum of all the kinetic and potential energies within the solid.

Two uncharged atoms exert forces on each other due to the repulsive forces between their electron clouds and the attraction between the protons of each atom and the electrons of the other.

At the equilibrium separation, , the attractive and repulsive forces are exactly in balance.

For spaces closer than the equilibrium separation, the atoms repel each other, and for spaces larger than this the atoms attract.

The equilibrium separation represents the minimum potential energy, and is therefore the preferred separation of the solid.

As the temperature of a solid or liquid increases, the kinetic energy of the atoms or molecules present within the system increases as the vibrations increase in amplitude. Potential energy will also increase slightly as the mean separation between the atoms increases slightly.

Internal energy for a gas

Particles in a gas are able to move freely, and the particles’ kinetic energy therefore takes the form of translational motion.

The particles move randomly with different speeds and directions inside their confined space, bounding off each other and the walls of their container as they do so.

The motion of the atoms or molecules gives them enough kinetic energy to move far apart.

As the separation increases, the force between the two atoms or molecules decreases.

The effect of intermolecular forces is small (zero for an ideal gas). This means that the potential energy component of the internal energy of a gas is very small.

If any system of gas particles is at a fixed temperature, there will be a distribution of kinetic energies among the molecules.

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution models this.

Internal energy during change of phase

When a material changes phase, it does not undergo any change in temperature. Therefore, the kinetic energy component of the internal energy does not change.

The potential energy, however, does change.

Brownian motion

Brownian motion The random movement of small visible particles suspended in a fluid due to collisions with much smaller, randomly moving atoms or molecules of the fluid

Brownian motion was first observed in 1827 by Robert Brown when he observed the motion of pollen particles in water.

Brownian motion can be observed with a microscope and a focused filament lamp.

In accordance with the kinetic model of matter, all particles above absolute zero in temperature are in constant motion. The movement cannot however be accurately predicted as there are so many particles moving.

Pattern of movement of solids, liquids, and gases

When a solid is heated it will experience a rise in temperature, and the kinetic energy of its particles will increase. As the material is solid, the position of each atom, ion, or molecule will not change, since the particles are held in place by interatomic or intermolecular forces.

The increase in kinetic energy will result in greater vibration of the particles in the solid around their respective equilibrium positions.

In a liquid, the same effect takes place. This time, a small amount of translational kinetic energy will be added to the increase in vibrational kinetic energy, since the molecules are now ale to move past one another from place to place.

In a gas, almost all of the kinetic energy is translational as the particles move from place to place,.

Aerosols

The smell of a perfume or air freshener quickly moves across a room. This movement, called diffusion, is not Brownian motion but instead convection.

Specific heat capacity

Specific heat capacity The specific heat capacity, , of a substance is the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of of the substance by . ()

When energy is supplied to a body of mass by heating, the kinetic energy of its particles will increase and its temperature will rise.

The amount that the temperature increases or decreases is proportional to the mass of the object, the specific heat capacity of the object, and the energy supplied.

where

- is the change in thermal energy ()

- is the mass of the body ()

- is the specific heat capacity of the object ()

- is the change in temperature ( or )

Example

The specific heat capacity of aluminium is

How much energy is needed to raise the temperature of of aluminium from to ?()

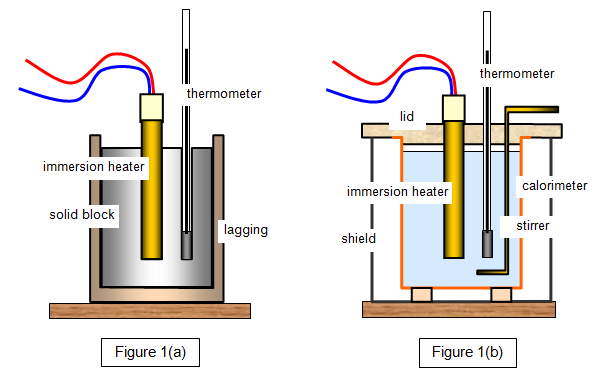

Determining the specific heat capacity of a material

- Insulate the material being heated and use a lid for liquids to ensure that as much as possible of the thermal energy supplied to the system is used to increase the temperature of the material. The temperature change should be as high as possible, , so as to reduce percentage uncertainty.

- Use an ammeter and voltmeter in the heating circuit to determine the power.

- Heat the material for a given time, until the required temperature change has been reached, and then calculate the energy expended with .

- Assuming that all of the energy transferred electrically is used to heat the material, use the principle of conservation of energy to give .

Specific latent heat

Specific latent heat of fusion () The amount of energy required to change the phase of of a substance from a solid to a liquid

Specific latent heat of vaporisation () The amount of energy required to change the phase of of a substance from a liquid to a gas

Changing phase

In order for a material to change phase from a solid to a liquid, or from a liquid to a gas, forces of attraction between atoms or ions in the material must be overcome.

In order to separate the particles, work must be done on the material.

The energy required to cause a change of phase is called the latent (hidden) heat.

Changes in temperature during phase changes

Experiments show that there is no change in temperature for some time at both the melting and the boiling point of a material, even thought thermal energy is being supplied.

When a substance changes phase the temperature remains constant so there is no increase in the kinetic energy of the atoms or molecules. The internal energy, however, does change, this is because a change in the forces between molecules during a change in phase produces a change in their potential energy.

Specific latent heat of fusion

When a substance is at its melting point, the energy required to change the phase of the substance from a solid to a liquid, or a liquid to a solid, is called the specific latent heat of fusion ().

The energy is taken in by the substance when it melts and given out by the substance when it freezes.

The term specific refers to the specific mass of from which the latent heat can be found for any mass.

The latent heat for a mass () is given by

Example

Given that the specific latent heat of fusion of water is , determine how much energy is required to convert of ice into liquid water.

Determining the specific latent heat of fusion

A known mass of ice is placed into two funnels, A and B.

The heater in arrangement A is connected to a power supply of known power P.

The control, B, is not connected to a power supply.

When water starts to drip from the funnels, the heater is switched on.

After 15 minutes the heater is switched off and the mass of the water in both beakers is measured.

The mass of the water in beaker B is the control value, which is to be subtracted from that of A to account for enegy accrued from the surroundings.

We then have that

Specific latent heat of vaporisation

When a substance boils or condenses, the specific latent heat of vaporisation () is the amount of energy required to change the phase of of the substance from a liquid to a gas or vice versa.

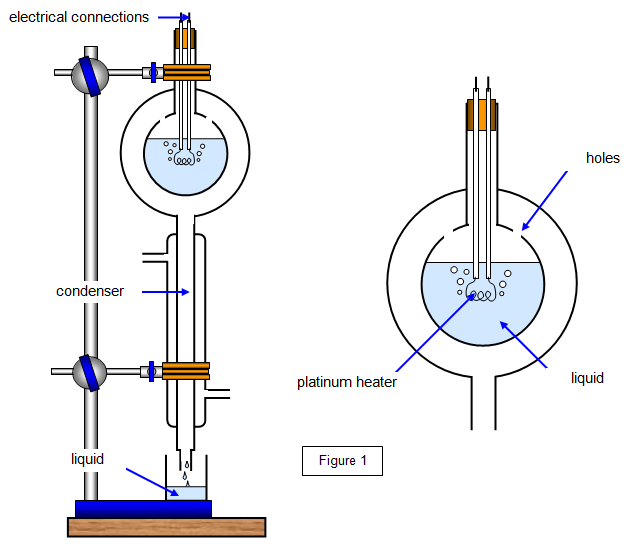

Determining the specific latent heat of vaporisation

The liquid whose specific latent heat of vaporisation is to be determined is heated to boiling point.

The vapour that is produced passes through the holes and into the condenser.

The vapour is collected for a time, , and its mass, , is determined.

At this point the current in the circuit is and the potential difference across the heating coil is .

By equating electrical energy supplied to thermal energy transferred we have where is the thermal energy transferred to the surroundings in time .

The potential difference across the heater and the current flowing through the heater are now changed to new values and respectively.

The mass of water vapour that is produced in the same time, , as before is noted and called .

This leads to .

The value of will be the same in each case, since the temperature of the apparatus has not changed.

Subtracting the two equations, we can eliminate , to give .

Since we know know the values, the specific latent heat of vaporisation is given by

The amount of substance

Moles

It is more useful to use the SI unit for the amount of a substance than to simply count the number of molecules in the substance.

One mole of any substance is the amount of the substance which contains as many atoms, molecules, or ions as there are atoms in of carbon-12.

The mass of one mole of a substance is called the molar mass.

The molar mass of a substance in grams is determined by its relative atomic mass, or the molecular mass, multiplied by the number of particles in one mole.

This number is the Avogadro constant

Molar mass of monatomic gases

Monatomic gases are composed of single atoms, such as helium. The mass of one mole of a monatomic gas is equal to its relative atomic mass.

Molar mas for diatomic gases

Nitrogen and oxygen are diatomic. Nitrogen and oxygen gas exist as molecules, each containing two atoms.

Nitrogen has a relative atomic mass of 14, and that of oxygen is 16.

Since they are diatomic, a mole of nitrogen gas () will have a mass of and a mole of oxygen gas () will have a mass of .

The relationship between Avogadro’s number (), the number of moles (), and the number of particles ()

One mole of a substance contains particles

moles of a substance contain particles

The number of particles present in a gas is equal to the number of moles multiplied by Avogadro’s number.

Example

Calculate:

a) The number of atoms in 3 moles of copperatoms

b) The mass of 3 moles of copper

Mass of mole is

Mass of moles =c) The number of atoms in 5 moles of neon gas

atoms

d) The number of molecules in 5 moles of oxygen gas

molecules

e) The number of atoms in 5 moles of oxygen gas

atoms

The kinetic theory of pressure of a gas

Ideal gas A gas that has internal energy only in the form of random kinetic energy

Mean square speed The mean value of the square of the velocity, , for a large number of gas particles moving randomly in a gas

Root mean square speed The square root of the mean square speed

Assumptions of the kinetic model of gas

- The gas contains a large number of particles

- The particles move rapidly and randomly

- All collisions are perfectly elastic, conserving kinetic energy

- There are negligible attractive forces between particles during collisions

- The time for a collision to happen is negligible compared to the time between collisions

- Particles have a negligible volume compared with the volume of gas in the container

Ideal and real gases

In reality the forces between the particles in a gas are not negligible and cannot be ignored. However, real gases will behave like ideal gases if they are at low pressure and a temperature significantly above their boiling point.

The internal energy of an ideal gas is composed entirely of the kinetic energy of its fast-moving particles, since we assume that there are no inter-molecular forces that could lead to additional potential energy in the system.

Pressure of gases

A gas in a container exerts pressure on the container walls due to collisions of gas molecules with the container walls.

Pressure is a vector quantity, since it has both a magnitude and a direction.

Pressure is defined as the force, , acting perpendicular to an area, . () ().

Gases are likely to have large numerical values of pressure because gas molecules may be travelling fast and there are huge numbers of them.

Atmospheric pressure is approximately , the reason that objects are not crushed under this pressure is that there are equal and opposite forces acting outwards.

Using the kinetic theory to obtain an equation for the pressure of an ideal gas

Suppose there are three molecules moving in a cubic box of side length . The molecules each have mass and are travelling at speed parallel to each of the axis respectively.

Let us consider only the first molecule, travelling parallel to the axis, and one wall of the box.

When the molecule hits the wall, it will rebound with velocity since since all collisions with the wall are perfectly elastic.

Initially, the momentum of the molecule is . Having collided with the wall and rebounded, its momentum will become , giving a change in momentum of .

The molecule will collide with the wall again after it has travelled a distance of across the box and back to the same wall.

The time it takes to do this is

By Newton’s second law of motion, the force, , exerted on the wall will be equal to the rate of change of momentum, so we have

From Newton’s third law, the molecule exerts an equal and opposite force on the wall.

The pressure on the wall is given by force over area, which in this case is .

Since the box is a cube, we can replace with the term to denote the volume, giving .

If there are gas molecules in the box the total pressure exerted on the wall will be given by the sum of the individual forces acting on the area of that wall.

In reality, the molecules move randomly in all directions, not in one direction as is modelled here.

Only changes of momentum in the direction perpendicular to the wall will cause an impact force on the wall.

For molecules travelling in the direction, the pressure exerted on the wall will be given by

This can be related to the mean value of the square of the component in the direction, , where

The pressure on one wall is then given by

Finally we must consider the motion of all the molecules that have components of velocity in the and axes.

If the velocity of a gas molecule is which can be resolved into components of and , it can be shown that

From the assumption of kinetic theory, the velocity is in a random direction, so the mean velocity component will be equal in every direction and . Hence it is possible to say that .

The total pressure is then , which can also be written

Alternatively, since the total mass of the gas is and since the density, , of the gas is , we obtain an expression for the pressure of an ideal gas as .

Investigating gases

Boyle’s law The volume of a fixed mass of gas is inversely proportional to the pressure exerted on the gas, under conditions of constant temperature.

If we have a gas at a pressure and volume , and we then change the conditions so that the gas has a new pressure and a new volume we can then say that .

Investigating Boyle’s law

Boyle’s law can be demonstrated with a measuring tube closed at one end and containing air above some oil.

The pressure on the oil can be increased by a foot pump, and the volume of air in the measuring tube can then be re-measured.

The values of pressure against volume once recorded can be plotted on a graph of against to give a linear plot, demonstrating the inverse proportionality.

The pressure temperature The pressure of a gas under conditions of constant volume is proportional to the absolute temperature of the gas.

Investigating pressure and temperature of a gas at constant volume

A fixed mass of a gas is heated in a sealed flask at constant volume.

The flask is placed in a water bath which is then heated to different temperatures and the pressure of the gas at each temperature is recorded.

When a graph of pressure against temperature is plotted, it will be linear with an intercept on the temperature axis of .

The ideal gas equation

Equation of state of an ideal gas The pressure of a gas, , with a volume, , when multiplied are equal to the molar gas constant, multiplied by the number of moles of gas, , and the temperature of the gas, .

Boyle’s law

Charles’ law

The pressure-temperature law

Collectively, these laws are called the gas laws.

The laws apply to most gases, but break down if the gas is close to its boiling point or at a very high pressure.

The laws also only hold for temperature values expressed in kelvin.

The ideal gas equation

In an ideal gas, there are no intermolecular forces between the gas atoms or molecules. An ideal gas will obey the gas laws exactly.

By combining the three gas laws we obtain for a fixed mass of gas.

The constant is dependent on the amount of gas present, the number of moles, . Introducing the molar gas constant, , we obtain , where .

For ideal gases which change their conditions of pressure, volume, or temperature, the equation can also be written as .

Example

A piston contains of gas at a pressure of and a temperature of .

The gas is then compressed to a new volume of under a pressure of .

What is the new temperature of the gas?

As the units are constant, the values can be inserted straight into the equation.

The Boltzmann constant

Boltzmann constant () A constant which relates the temperature of a gas to the mean translational kinetic energy of the particles in the gas. It can also be regarded as the gas constant for a single molecule.

Example

Neon is a monatomic gas with a molar mass of . If it is kept in a cylinder of volume at a pressure of and a temperature of , find:

a) The number of moles of neon in the cylinder

Substituting the values gives

molesb) The mass of neon in the cylinder

Mass of neon = number of moles x mass of one mole

c) The number of atoms of neon in the cylinder